THE ISA UPANISAD

An Attempt at

Interpretation

Arunava Gupta

The Isa Upanisad appears to be an abstruse text, with many

terms and concepts difficult to pierceTP[1]PT and commentators varying considerably in

their interpretations. In this paper, an attempt is made to decipher the

meaning of the Isa drawing from the ‘resources’ – ideas and teachings - of the

other seminal texts of Hinduism such as the Bhagavad-Gita and the Srimad-Bhagavata

which may, besides aiding in our understanding of the text, also facilitate a

more constructive engagement with it.

The passage beginning īśā vāsyam idaṃ sarvaṃ to kurvann

eveha karmāṇiTP[2]PT

In the very first verse of

the Isa itself (right after the santi-patha or the peace invocation) is

encountered a ‘difficult’ term. Some scholars seem to opine that ‘īśā vāsyam

idaṃ sarvaṃ’

means ‘all this is enveloped by the Lord’ while others feel that ‘dwelt in’

might be more appropriate[3]PT. While admitting that

these two meanings need not be mutually exclusive- surely they are not, as lines

such as sarvāṇi bhūtāny ātmany, ‘all beings within the Self’ (IsUp_6) quite clearly demonstrate - one feels

that, as is the general consensus, the latter reading is more apposite in the

context of the work in question. The maturest products of the Hindu spiritual

mind have always laid more stress on the immanent aspect of GodTP[4]PT. Krishna ,

for instance, in the Bhagavata, exhorts Uddhava to seek sole-refuge (Eka-Sarana)

in Him who is ‘sarva dehinam’, the ‘Soul of all embodied beingsTP[5]PT’. The great preachers of

the devotional Bhakti movements are also no exception to this. Sankaradeva,

illustrating the all-pervasive immanence of the Lord, says, “In Thy sva-rupa

as Isa, O Hari, Thou art seated in all containers (bodies), just as the

sky is contained within all pitchers[6]PT”. Therefore, rather than

‘all this is enveloped by the Lord’, the more appropriate translation would be

‘all this is dwelt in by the Lord’ or ‘within all beings, the Lord resides’.

That would bring out the immanence of God more clearly. The Lord, the atman

(Self) of the world, is present (as the supreme consciousness) within ‘whatever

living being there is in the world’. He is not merely a transcendent God but

also an immanent Lord.

It is at this point that

one feels that, although not considered (in certain editions) to be an integral

part of the mula text of the Isa, the santi-patha (purnamadah)

or ‘peace-invocation’ prepended to it, seems to determine the ‘agenda’, so to

speak, of this Upanishad. The first verse’s īśā vāsyam idaṃ sarvaṃ follows beautifully from it. The higher wisdom, we get an inkling, is set to be

revealed within the ‘frame of reference’ of an immanent Self. It is likely that

purnam here is an epithet of the Lord. As regards meaning, it seems to

have a great connection with the famous catuhsloki contained in the

Srimad-BhagavataTP[7]PT. That the (complete) Lord

alone existed in the beginning (pre-creation), that it is only He who is to be

perceived within the entire creation, the transcendent God becoming immanent,

fully or immutably, within His creation[8]PT and that, at the end,

‘when the full is subtracted from the full’ – when He withdraws His own

creation – it is He alone who remains, immutably again, as the ‘resultant’ (avasisyate),

as it were – this seems to be the eternal truth conveyed by these verses.

But, our seer seems to be more concerned with the ‘middle

stage’ implied in the invocation. This is understandable as for the embodied

beings, the immediate concern is not so much with things occurring pre-creation

or post-creation, but rather with the path one ought to tread presently. What

is the ‘good path to the felicity’ – the supathā in the final stanza -

for man to follow in this world that will lead to the Highest Good?

Now, the Isa is a short Upanisad. Therefore, it

comes straight to the point or, at least, that is what the reader is led to think.

A view is immediately put forth that ‘as all this is permeated by the Lord’ (in

continuation of the line of thinking in the santi-patha), therefore, men

should ‘enjoy leading a life of renunciation’, doing only ‘niskama karma’,

desireless (ritual) action according to some traditional commentators, and should

not ‘aspire for others’ wealth’. This is, without doubt, advice practical and

sound, especially for the man of the world, but, to the critical ‘connoisseur’

of the Upanisad, it still does not quite taste of the higher wisdom one expects

from the ‘End of the Vedas’. Which leads one to suspect if it is a view put

forward simply for demolishing.

Proponents of the theory

of karma (works) are quick to leap on this, however, and, in the next

verse, kurvann eveha karmāṇi

(‘verily by doing works alone’).

The exponents of the Arya Samaj feel that this highlights the supremacy of the

performance of Vedic karmaTP[9]PT.

It must be noted that ‘karma’ here is interpreted by many commentators

as the religious duties enjoined by the VedaTP[10]PT. And it may well be so.

But is this really the verdict, the siddhanta, of the text or merely a

tentative thesis (for demolishing) put forward by the seer himself or some purva-paksa?

Could it be a ‘lower truth’ - a stepping stone to higher things - or maybe, just

a part of the dialogue as in the Gita, for instance?

The answer seems to lie in the scoffing tone of the

author. Now, tone is one thing that not all translators try to grasp, but it

seems necessary to factor in this important aspect into the translation as,

thereby, many subtle shades of (hidden) meaning may be revealed. “Simply perform

desireless works and live happily for a hundred years, jijīviṣecchataṃ samāḥ (is there anything more that you want!)” This

scoffing nature of the tone of the preceptor assumes significance in the light

of the fact that many prayers in the Vedas were largely petitions for long life,

etc. Thus, by this tentative ‘assertion’, the seer seems to be mocking at those

who, regarding the Lord as an ordinary deity, may be prone to seeking such

material gains from Him. They would be the ones whose minds have not yet been fully

soaked in the Glory of the immanent God.

Of course, again, this ‘path’

might also be a way of testing the student-seeker, in the manner of a Yama

testing Naciketas, for instance, or Krishna ,

Arjuna. If the seeker is satisfied with this ‘path’, and goes away (in the

manner of a Bali in the Chandogya, for

instance), then there is no need for any upward ascent[11]PT.

The passage beginning

asuryā nāma te lokā

In this, it appears, there

is the censure of ‘all those people who kill the Self’. Although it is not explicitly

specified who these people are, it may safely be assumed from the internal

evidence afforded by the text (e.g., IsUp_9, 12) that these are the people who

have not grasped the correct knowledge of the Reality, perhaps as a result of

betaking to false paths. In Muller’s rendering, they are the ones “Twho perform works, without having arrived at a

knowledge of the true Self”.T

In any case, they are said

to fall after death into worlds ‘demonic’ or ‘sunlessTP[12]PT’ enveloped by ‘blinding

darkness’. This is in consequence of their spiritual suicide. In Vedanta,

ignorance is always dark and death-like. People who do not follow the true, sun-lit

path will most certainly grope in darkness.

‘Killing’ the Self would

mean the misidentification of (imperishable) self with (perishable) bodyTP[13]PT, an ‘act’ more sinful than

it is fatal for, thereby, Spirit is reduced to matter. The in-dwelling Lord, eternal,

undying, unborn, is reduced to lowly impermanence. For this heinous crime

against Spirit, the individual self is condemned ultimately to be ensnared in

the vicious cycle of births and deaths.

This verse, one feels, is some sort of a link

between the ‘lower truth’ pronounced in IsUp_1, 2 and the higher wisdom to

follow. Before moving on to illuminate the mind of the aspirant, the seer seems

to consider it necessary to alert the seeker to the danger that attends on

imperfect knowledge and/or a false path. That may also be his way of

repudiating the notion of ‘desireless works’ advanced tentatively in the

earlier verses.

The passage beginning

anejad ekaṃ manaso to tad ejati tan naijati

After negating the theory of works, the positive

instruction here begins. These verses seem to be truly Vedantic in character. The

inconceivable, inestimable potencies of God are first revealed. These are

beyond the grasp of intellect. He is no ordinary person. Even the gods cannot

catch Him. He is peerless. He seems to be a transcendental Person. He is

both transcendent and immanent. Within Him all causal processes (of the cosmos)

go on (‘Matarisvan places the waters’) and yet how supremely amazing it is that

He Himself is within this causal process (tad antar asya sarvasya)!

The passage beginning

yas tu sarvāṇi bhūtāny to sa paryagāc chukram

The teaching in verses IsUp_6-8 seems to be more

prescriptive in nature. We must see the Lord in all (and all in the Lord).

Knowing is not enough; we must see (anupaśyati). Once this oneness is

internalized, delusion, sorrow et al simply vanishes. All is the Lord.

Whom shall we fear, whom shall we hate.

The Self will then not seek to ‘hide’ from us (na

vijugupsate) i.e. following the true path, ignorance is removed; blessed

with the seer’s vision, we would then see the Lord seated in our heart (inmost

consciousness). ‘It does not hide from him’ seems to be the immediate meaning.

But, of course, ‘he does not hate anybody’ is also an excellent interpretation

which, however, would follow automatically from the more immediate meaning.

IsUp_8 seems to lay down

the ‘benefits’ of following such a path. Perhaps the idea conveyed here is that

he who has acquired true knowledge of the Self

‘reaches’ the Self, that ageless, eternal One, that ‘wise sage’ who ‘disposed

all things rightly for eternal years’. He realizes that like the Lord, he too

is ‘bright, incorporeal, scatheless, pure’. He is really ‘without sinews’,

‘without muscles’. ‘I am not this body’– realization dawns. Body is

un-eternal.

The passage beginning

andhaṃ tamaḥ

praviśanti to saṃbhūtiṃ

ca vināśaṃ ca

This section seems to be concerned with determining

the parameters of true worship or upasana. We must exercise

discrimination in our process of upasana. The approach of the seer is as

discriminating as that of the swan. Equipped with true vidya, only the

Lord must be worshipped. Only Spirit, not matter.

True knowledge (vidya) is knowledge

of the Self, the Lord (as already taught by the seer in the preceding verses). Similarly,

the true unmanifested (asambhūti) is really the Lord, the Self. But, if

one were to commit the fatal mistake of (falsely) identifying the real with the

unreal, then, again, as in IsUp_3 (asuryā nāma te lokā), one is condemned

to fall into the andhaṃ tamaḥ, the

‘blinding darkness’ of the ‘sunless worlds’.

They who are steeped in

rank ignorance ‘make a cult of nescience’. They degrade themselves spiritually by

such worship but receiving the counsel of the saints and seers, they would

correct themselves. They did not know. In that way, their ignorance holds them

in good stead. But the middle category of half-learned persons who have crossed

the stage of total ignorance (by possessing imperfect knowledge) yet have not

grasped the correct knowledge of Reality (but would never admit it, unlike the

totally ignorant,) are irredeemable. Their minds are closed. They plunge, as it

were, into greater darkness. The Bhagavata talks of such ‘godless people’ who, shrouding

their Self in ignorance, mistake karma for knowledge and fall down deep

into hellTP[14]PT.

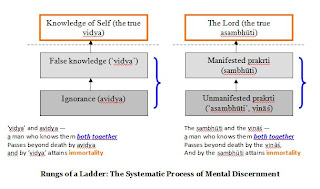

The following diagram may help us to analyze the

ideas contained in these verses with some clarity. The shaded boxes are the

‘rungs’ of a mental ladder corresponding to the upward climb of the intellect

through a systemic process of discernment.

To obtain the true knowledge, shedding ignorance is not sufficient. We must also come out of false knowledge. Similarly, rejecting matter (in the process of upasana) is not enough; we must also reject the material manifestations, in order to receive the embrace of the Pure Spirit. If we do not endeavor to understand these concepts and entities ‘both together’, then we will fall. If we are stuck in a ‘higher’ stage of ignorance, for instance, we fall harder than the ones below on the ‘lower rung’ of this (mental) ladder. But if we climb ‘both together’ these two ‘rungs’ of avidya and false-vidya, then we attain ‘immortality’, the true knowledge of the Self. Then, truly we transcend ‘avidya’ (the dotted line in the figure above). From this point, there is no fall.

In other words, in the case of avidya-vidya discernment,

first we (1) eliminate total ignorance, climb up, then (2) eliminate

false-knowledge, climb up and, finally, True Knowledge is reached.

In the second set of verses, ‘asambhūti’ tends

to remind us of the ‘unmanifested prakrti’, the lower, non-eternal avyakta,

mentioned by Krishna in the Gita[15].

Emergence and dissolution are the twin-processes of the material realm. Though,

from the stand-point of the process of cosmic evolution, unmanifested prakrti

may occupy a higher position than the material manifestations of God such as

the demi-gods, still, for the process of mental discernment, inverse has

to be the case. We do not rise up to (soul-less) matter, rather climb up

from it. Therefore, unlike in the analysis of the first pair (avidya

and vidya), we first have to invert the ‘ladder’. Then the discernment

begins as before: first we (1) reject matter, climb up, then (2) reject ‘matter

plus soul’, climb up and finally the non-dual Spirit is reached.

In both cases (avidya-vidya, asambhūti-sambhūti)

we must climb ‘both together’ (vedobhayaṃ saha). Otherwise, little learning will prove to be

dangerous thing. Multiplicity will be perceived rather than unity. And the

consequences in both cases are far more hellish.

In order to bring out the meaning of this abstruse

passage more clearly, the following translation is proposed: -

“They who worship

ignorance enter into blinding darkness

They who delight

in false-knowledge into darkness greater still || IsUp_9 ||

“Quite other[16]

is the result obtained from false-knowledge

Other (of course) is the result obtained

from ignorance

When we do not know BOTH TOGETHER || IsUp_10 ||

“But, if we know BOTH of them–

false-knowledge and ignorance –TOGETHER, then

Climbing up from ignorance to false-knowledge, one crosses death

AND climbing up from false-knowledge

to True Knowledge, attains to immortality” || IsUp_11 ||

“They who worship prakrti, the false unmanifested, enter

into blinding darkness

They who delight

in worshiping the material manifestations into darkness greater still ||

IsUp_12 ||

“Quite other[17]

is the result obtained from material manifestations

Other (of course) is the result obtained

from prakrti, the false unmanifested

When we do not know BOTH TOGETHER || IsUp_13 ||

“But, if we know BOTH of them– material manifestations and matter –TOGETHER,

then

Climbing up from matter to manifestation, one crosses death

AND climbing up from manifestation to the

True Unmanifested- the Pure Spirit -attains to immortality” || IsUp_14 ||

Upasana,

translated rather loosely as ‘worship’, is a subtle but critical process. False,

unscientific upasana can degrade the mind towards matter instead of

elevating it towards Spirit. Therefore one must first engage in tattva-vicara,

a thorough analysis of the ‘eternal’ and the ‘non-eternal’.

The passage beginning

hiraṇmayena pātreṇa to pūṣann ekarṣe yama

The teaching now appears to be moving swiftly towards

its final climax. There is a sudden acceleration[18];

the tone of the seer seems to be suddenly charged with a new energy. It is one

associated with intense emotionalism. The poet-seer’s heart is a-thrill with

joy (so 'ham asmi!) Are we seeing the germ of Bhakti in the Isa?

The seer sees the Lord as

a (transcendental) person; he sees the ‘face’ of God as being covered, hidden

by a ‘golden vessel’. ‘Hidden’ is perhaps more apposite, in tune with vijugupsate

in an earlier verse (IsUp_6). Clearly,

this ‘vessel’ is playing an obscuring role for, unless something obscures, one

would not entreat tat tvaṃ pūṣann apāvṛṇu. As the passage itself says, it is masking

(apihitaṃ)

the face of the True, ‘the nature of the True’ (satyadharmāya).

In the light of what has

already been said in the earlier verses, we are almost irresistibly drawn

towards the conclusion that in this there is the repudiation of the doctrine of

karma or activism. According to the Monier Williams' Sanskrit-English

Dictionary, pātrīya means ‘a kind of sacrificial vessel’. In the Brihadaranyaka,

there is indeed a reference to a golden sacrificial vessel[19]PT. ‘Works’ (karma-kanda)

is blocking true spirituality, the realization of the Self, atma-tattva;

‘hiraṇmayena pātreṇa’ is the poet-seer’s way, perhaps, of expressing

this.

An important conclusion that

could be drawn in the light of ‘vijugupsate’ earlier is that the

doctrine of the ‘golden vessel’ is incompatible with the realization of the

immanent Glory of the Lord, a barrier to viewing the Lord in the heart of beings[20]PT. As soon as that barrier

is removed, the realization (of this immanence) dawns – “I am He!TP[21]PT”

The passage beginning

vāyur anilam amṛtam to agne naya supathā rāye

In these two climactic verses, we see the ‘final

movement’ of the Upanisad (in Sri Aurobindo’s words). The ‘golden vessel’ - the

doctrine of works - has now been removed. The death-like ignorance is dying; deha-buddhi,

the false identification of the self with body, is disappearing; nitya-anitya

vastu-viveka, discrimination between eternal and non-eternal, has dawned.

The seeker will now

surrender completely reposing firm faith in the Lord. We can almost hear at

this point the preceptor saying, as in the Gita, “The Lord abides in the hearts

of all beings. Flee unto Him for shelter with all Thy being, O BharataTP[22]PT”.

Some commentators have pointed out that that these

lines are supposed to be uttered by a man in the hour of death. The seer is suddenly

seen to be making preparations to leave the mortal coil. This physical

interpretation is somewhat surprising considering the fact that in Vedanta, the

unreal is verily death, the darkness is verily death and, so, if we pick up

this thread of understanding, then it would not be difficult to accept that

ignorance is verily death. Assuming that the previous verses, especially IsUp_9-14,

were designed to remove the ignorance of the aspirant which indeed they looked

like doing, then it is quite apparent that rather than the seer, it is the

death-like ignorance of the seeker that is now going. He now identifies himself

neither with the gross body nor with the vital air(s) but with the Self.

‘Krato’ seems to refer not to ‘deed’ as in some translations but rather to the

Lord. In the Gita (9:16), Krishna says, “I am kratu

(the ritual action)”. Similarly, ‘kritam’ would refer to the Supreme

Truth or God Himself. Such a belief

would be strengthened by Krishna ’s ‘Fix thy

mind on Me’ (manmana bhava) in the Gita which, like in the Isa, also comes

in the final stage of the Teaching.

The words agne naya supathā rāye again look

to be the words not of the preceptor but of the pupil. “O God! O Agni! Lead us

by the good path to the felicity”. ‘Agni’ here most likely is an epithet used

to address the Lord in His capacity as the giver of light or the dispeller of

ignorance– the supreme teacher, the Guru. The student-seeker thus appears to

have taken sole-refuge in his Preceptor: -

“Lead me from the unreal to the real! Lead me from

darkness to light! Lead me from death to immortality![23]”

The whole of the Isa, in fact, appears to be

structured in the manner of a dialogue. Of course, in texts as pithy and

aphoristic as the Isa, the speaker would never be indicated, but a close

reading of the text does lead to a feeling that this is not a monologue here; there

are two parties necessarily involved in this discourse and these two must

inevitably be the pupil and the teacher, for the very etymology of ‘Upanishad’ suggests

‘sitting down near a teacher to receive instruction’. Krishna

and Arjuna in the Gita is the best example of such a combination. In Hindu

thought, spiritual knowledge is best transmitted through this dialogue between

teacher and student. In view of these factors, viewing the Isa as a soliloquy

would not be, we feel, doing full justice to this important text.

This last verse again is

striking, ‘lead us along the good path to riches […] and the highest song of

praise, we shall offer to you’. This seems to be a radical transformation

of the traditional Vedic prayer[24]PT seeking material benefits

to one that seeks now only spiritual ‘gain’. Hereafter, it seems, prayer is to

be the only offering[25]PT.

The Path of the Isa

Upanisad

From this discussion, the following may be said to

be a rough outline of the Path suggested by the Isa: -

- Know the Lord of Infinite

Glory as immanent in all beings, seated in the hearts of all – (īśā

vāsyam idaṃ sarvaṃ, sarvabhūteṣu cātmānaṃ)

- Know the body as

destructible (bhasmāntaṃ

śarīram) and only the Lord,

the Self, as eternal (asnāviraṃ, chāśvatībhyaḥ)

- Finally, surrender oneself completely to the

Lord forsaking all karmas (symbolized by hiraṇmayena pātreṇa);

seek sole-refuge (Eka-Sarana in the GitaTP[26]PT and the

BhagavataTP[27]PT) in Him.

Such a siddhanta or verdict would be fully

consistent with the key utterances and highest teachings of both the Gita and

the Bhagavata.

Only when he takes to this supremely beneficial

path (supathā rāye) will the Grace of the Lord be bestowed on the seeker;

sorrow and delusion then would come to naught (ko mohaḥ kaḥ

śoka).

Significance of the

Isa in Hindu spiritual thought

The Isa Upanisad is certainly a monumental text in

so far as it seems to provide the germ for the full development of the path of

Bhakti, the maturest phase of which is witnessed in the texts such as the Srimad-Bhagavata,

the ‘ripened fruit of the Vedic tree’. The Isa also seems to be the forerunner

of the central (Bhaktic) doctrine of Grace of the Lord contained in the Bhagavad

Gita. It is in a way the Gita in miniature[28].

Krishna is vedanta-gayaka, the ‘singer

of the Vedantic verse’ and He certainly sings many tunes from the Isa.

Profound would be the implications of the Isa at

the level of upasana. Worship of prakrti or demi-gods would not find

sanction; karma-kanda is sure upbraided.

Hindu spiritual thought, it may be affirmed in the

light of this interpretation, is a continuum. The Vedanta teaches that the

transcendent and the immanent must be reconciled but the stress is definitely

on the Self, the immanent, and this central Vedantic theme persists even in the

maturest phases of evolution of Hindu spiritual thought.

TP[1]PT

“This Upanishad, though apparently simple and intelligible, is in reality one

of the most difficult to understand properly” (Max Muller)

TP[2]PT

The transliteration of the verses and the scheme for numbering of the same is

from GRETIL etexts

The portions of translations quoted throughout, either

in original or in re-phrased form, are mostly from translations of the Isa by Olivelle,

Muller and Sri Aurobindo

TP[3]PT

Max Muller’s translation, for instance, conveys such a sense in this regard,

“All this […] is to be hidden in the Lord” HTUhttp://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe01/sbe01243.htmUTH

There also

appears to be another reading and that is ‘all this envelops the Lord’.

According to Sri Aurobindo, “TThere are three possible senses ofTT TTvasyam, “to be clothed”, “to be worn as garment” and “to be

inhabited”. The first is the ordinarily accepted meaning. Shankara explains it

in this significance […] The image is of the world either as a garment or as a

dwelling-place for the informing and governing Spirit. The latter significance

agrees better with the thought of the Upanishad.”

TP[4]PT

Radhakrishnan, in his translation of the very first mantra (the

‘peace-invocation’) comments that ‘Brahman is both transcendent and immanent’ (cited

in Interpreting the Upanishads, Ananda Wood, 2003, p. 4). But

the stress seems to be more on the immanent. If the first few words of the next

verse (IsUp_1) were to be read as “The Lord resides in every being of this

[creation]”, it would follow quite logically from the earlier verse.

TP[6]PT

‘isa svarupe hari sava ghate baithaha jaisana gagana viyapi’. Early History

of the Vaisnava Faith and Movement in Assam

nānyad yat sad-asat param

paścād ahaḿ yad etac ca

yo 'vaśiṣyeta so 'smy aham (2.9.33)

TP[8]PT

It is tempting in this context to bring in the theory of incarnation (avataravada)

of God. Reading the Upanishad in a Bhaktic or Bhagavatic light, it would

perhaps not be going too far if one were to view the immanent God (purnam

idam) residing in all creatures as a kind of avatara. In the

Bhagavata (11.4.3), it is found that, “When the primeval Lord Nārāyaṇa

created His universal body out of the five elements produced from Himself and

then entered within that universal body by His own plenary portion, He thus

became known as the Puruṣa” [avatara]. HTUhttp://vedabase.net/sb/11/4/enUTH

Interestingly, in the Isa also, we find the word ‘purusa’,

pyo 'sāv asau puruṣaḥ so 'ham asmi (IsUp_16)

TP[10]PT

The Nine Upanishads, Isa and the others, Hari Krishna Dasa Goyandaka (Int.),

Gita Press, Gorakhpur

TP[11]PT

To digress further, this mocking tone in the second verse apart, there also

appears to be a paradoxical tune to the first as well. If indeed “all beings

are the Lord”, if all things and properties be, in truth, the Lord’s, then how

can one possibly renounce (tyaktena) in the full import of the term?

Renunciation, if it were to be true, would assume a person to be really in

possession of something but, if, that ‘something’ is in actuality the Lord’s,

then how can there be genuine renunciation? Renunciation, therefore, has to be

unspiritual, a ‘lower truth’, and tyaktena bhunjitha (interpreted as ‘niskama

karma’ by some) cannot be the real path.

TP[12]PT

‘Sunless’ indeed seems to be more apposite, in the context of verses such as IsUp_16.

According to Sri Aurobindo, “The third verse is, in the thought structure of

the Upanishad, the starting-point for the final movement in the last four

verses […] The prayer to the Sun refers back in thought to the sunless worlds

and their blind gloom, which are recalled in the ninth and twelfth verses”

TP[14]PT

“These godless people hate Lord Hari – their very indwelling self who abides in

the bodies of others as well (as their Soul); and fixing their attachment to

their mortal body….fall down deep into hell.

“Those who have not grasped the correct knowledge of

Reality and have crossed the stage of total ignorance (by possessing imperfect

knowledge) regard themselves as non-momentary (permanent); […] such persons

(who thus follow a suicidal path) ruin themselves.

“Such people shrouding their Self in ignorance and

with their desires unrequited, mistake ignorance (karma) for knowledge.

Being thwarted in achieving their objects and their hopes and wishes being

frustrated by the Time-Spirit they ruin themselves (and suffer misery)”.

The

Bhagavata Purana, Translated and Annotated by Dr. GV Tagare, Part V, Motilal

Banarsidass, 1978, p. 1923, Slokas 15-17 (11.5). It is striking that the words

used to describe such people are ātma-hano 'śāntā. Significantly enough,

these were spoken by a ‘master of atmic lore’. The translator (Tagare)

makes a note of this connection with the Isa in the footnote. Svami Bhaktivedanta

Prabhupada also notes this fact in his commentary on the passage in question.

See HTUhttp://vedabase.net/sb/11/5/17/enUTH

[15]

“Here the unmanifested [avyakta] is prakrti”, Bhagavad Gita, Radhakrishnan

(Tr.), p. 233, ‘Yoga of the Imperishable Absolute’ (8.18)

[16]

‘Quite other’ emphasizes the ‘harder fall’

[17]

‘Quite other’ emphasizes the ‘harder fall’

[18]

There is, at this point, a sudden ‘shower’ of exclamation marks in the

translations!

TP[19]PT

“Verily Day arose after the horse as the (golden) vessel, called Mahiman (greatness),

which (at the sacrifice) is placed before the horse”.

“Two vessels, to hold the sacrificial libations, are

placed at the Asvamedha before and behind the horse, the former made of gold,

the latter made of silver. They are called Mahiman in the technical language of

the ceremonial”. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, First Adhyaya, First Brahmana, Max

Muller (Tr.)

- When

a man sees the Self in all beings, He (the Self) does not ‘hide’ from him;

- The

hiraṇmayena pātreṇa (theory of karma) is keeping

the Self hidden from man; He is, as it were, ‘hiding’ from him;

Therefore, by logic, a probable reason could be that

man is not seeing the Self in all beings (not conceiving of the Lord as being

immanent in all beings). And, if that be the case, the direct cause would be

that hiraṇmayena

pātreṇa

(theory of karma). An affirmation of such a view comes from the Srimad-Bhagavata

(10.86.47), hrdi-stho 'py_ati-dura-sthah karma-viksipta-cetasam. Also,

in 11.12.14 of the same text, Krishna asks

Uddhava to renounce both pravrtti and nivrtti types of karmas and

then take sole-refuge in Him who is the Soul of all beings,. ‘tasmattvamuddhavotsrjya

codanam praticodanam / pravrttinca nivrttinca srotavyam srutameva ca…’

TP[21]PT

Rather than ‘I am He!’, the more accurate rendering of so 'ham asmi

in this context would perhaps be ‘that (Lord) is (actually) this ‘me’!’

as the supreme truth (purnam adah purnam idam).seems to point inwards

rather than outwards.

TP[22]PT

‘isvarah sarvabhutanam hrddese ‘rjuna tisthati […] tam eva saranam

gaccha sarvabhavena bharata’, Bhagavad Gita, Radhakrishnan (Tr.),

pp. 374-375

[23]

Brihadaranyaka (1.3.27)

TP[24]PT

“Through Agni man obtaineth wealth, yea, plenty waxing day by day…”, Rig Veda,

Hymn I, Book I, RTH Griffith (Tr.)

TP[25]PT

“The wordT TvidhemaT Tis used of the ordering of the sacrifice, the disposal of

the offerings to the God […] Here the offering is that of completest submission

and the self-surrender…”, Sri Aurobindo, op cit

TP[27]PT

‘mamekameva saranamatmanam sarva dehinam / yahi sarvatmabhavena maya syah

hyakutobhayah’ Srimad-Bhagavata (11.12.15)

[28]

Strikingly enough, the Isa has eighteen verses and the Gita, eighteen chapters.